Lower thresholds for blood transfusions during cardiac surgery have proven to be safe and provide good patient outcomes compared to traditional thresholds, according to the largest research study ever performed in this area. The lower or “restrictive” threshold also can help reduce the amount of blood transfused and money spent for each procedure.

The randomized trial involving more than 5,000 patients at 74 cardiac care centres in 19 countries found no clinical or statistical difference in the four important patient outcomes chosen to determine whether contemporary restrictive practices provided better or worse patient safety and outcomes than traditional liberal practices. The chosen indicators included death, heart attack, stroke or new kidney failure.

The study found that the restrictive approach reduced the number of patients who received transfusions by 28 percent and reduced the amount of blood transfused by approximately 30 per cent.

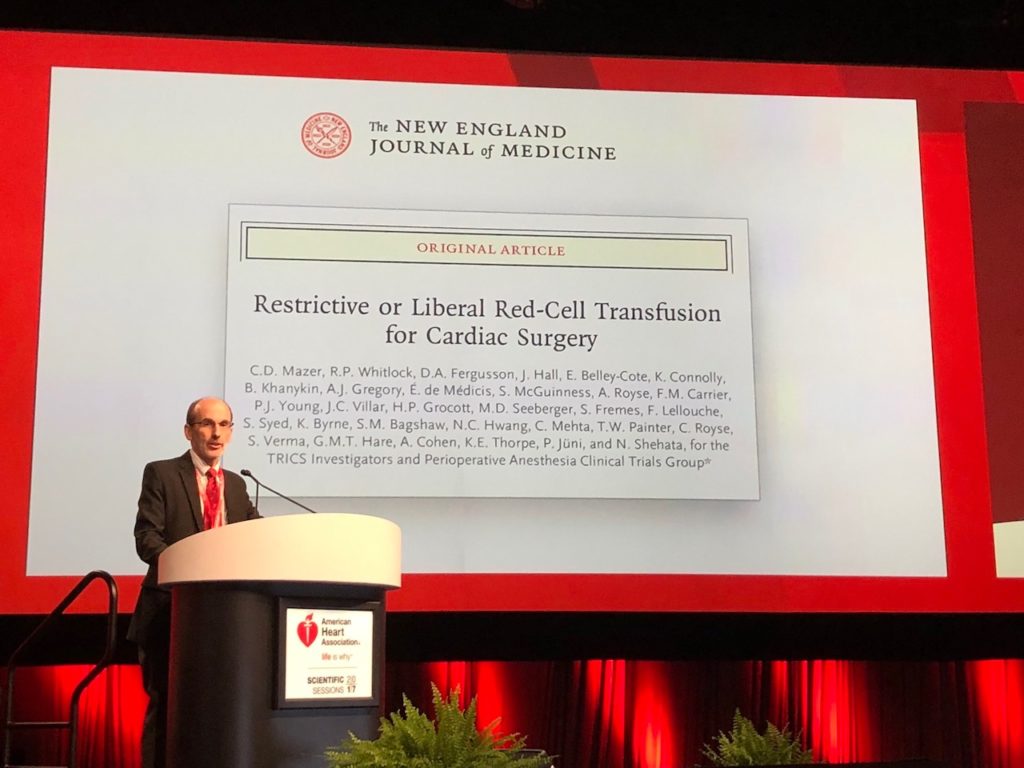

The findings were presented at the American Heart Association’s annual meeting in Anaheim. Calif., by Dr. David Mazer, an anesthesiologist at St. Michael’s Hospital and associate scientist in its Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science. They were published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

According to Dr. Mazer, physicians who practice the liberal transfusion approach tend to give blood transfusions early in the surgery to prevent patients’ hemoglobin level from falling. Hemoglobin is the protein that allows red blood cells to deliver oxygen to body tissues. Physicians who practice a restrictive approach tend to wait longer to see if the hemoglobin level remains stable or if the patient has excessive bleeding.

Dr. Mazer said the study was important because transfusion practices vary widely around the world and because there are known risks to blood transfusions and to acute anemia (falling hemoglobin levels). Other studies have shown that restrictive transfusion practices can reduce the number and volume of transfusions, but this is the first research, he said, to definitively show it is equal to higher thresholds in terms of patient safety and outcomes.

“We have shown that this approach to transfusion is safe, in moderate- to high-risk patients undergoing cardiac surgery,” Dr. Mazer said. “Such practices can also reduce the number of patients transfused, the amount of blood transfused, the impact on blood supply and costs to the health-care system.”

This study received funding from the Canadian Institutes of Heart Research, Canadian Blood Services, the National Health and Medical Research Council in Australia and the Health Research Council of New Zealand.

This paper is an example of how St. Michael’s Hospital is making Ontario Healthier, Wealthier, Smarter.

About St. Michael’s Hospital

St. Michael’s Hospital provides compassionate care to all who enter its doors. The hospital also provides outstanding medical education to future health care professionals in more than 29 academic disciplines. Critical care and trauma, heart disease, neurosurgery, diabetes, cancer care, care of the homeless and global health are among the Hospital’s recognized areas of expertise. Through the Keenan Research Centre and the Li Ka Shing International Healthcare Education Centre, which make up the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, research and education at St. Michael’s Hospital are recognized and make an impact around the world. Founded in 1892, the hospital is fully affiliated with the University of Toronto.